09 Aug Public Interest Litigation (PIL)

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) – UPSC Law Optional (Paper 1)

Article 226

Locus Standi

Epistolary Jurisdiction

Continuing Mandamus

Social Action Litigation

Environmental PIL

Bonded Labour

Prison Reforms

Right to Food

Police Reforms

Guidelines against Abuse

Table of Contents

2) Meaning, Objectives & Constitutional Location

3) Evolution of PIL in India: Phases

4) Locus Standi & Access to Justice Innovations

5) Epistolary Jurisdiction & Suo Motu

6) Continuing Mandamus & Court-Monitored Compliance

7) Major Subject-Areas of PIL

8) Doctrinal Architecture: Standards & Tools

9) Limits, Abuse & Safeguards

10) Drafting & Strategy for PIL (Exam-oriented)

11) Landmark Case-Law Capsules (1–3 lines)

12) Critiques, Course-Corrections & Future of PIL

13) Selected Previous-Year Themes (Law Optional)

14) Probable Questions (Prelims & Mains)

15) FAQ & Quick Tips

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) – Purpose at a Glance

ACCESS

• Locus expanded

• Letters treated as petitions

• Class-based harms addressed

• Amicus & fact-finding missions

ACCOUNTABILITY

• Executive inaction corrected

• Standards for prisons, labour

• Transparency directions

• Independent oversight

REMEDIES

• Writs under Arts. 32/226

• Guidelines where law is silent

• Continuing mandamus

• Compensation & monitoring

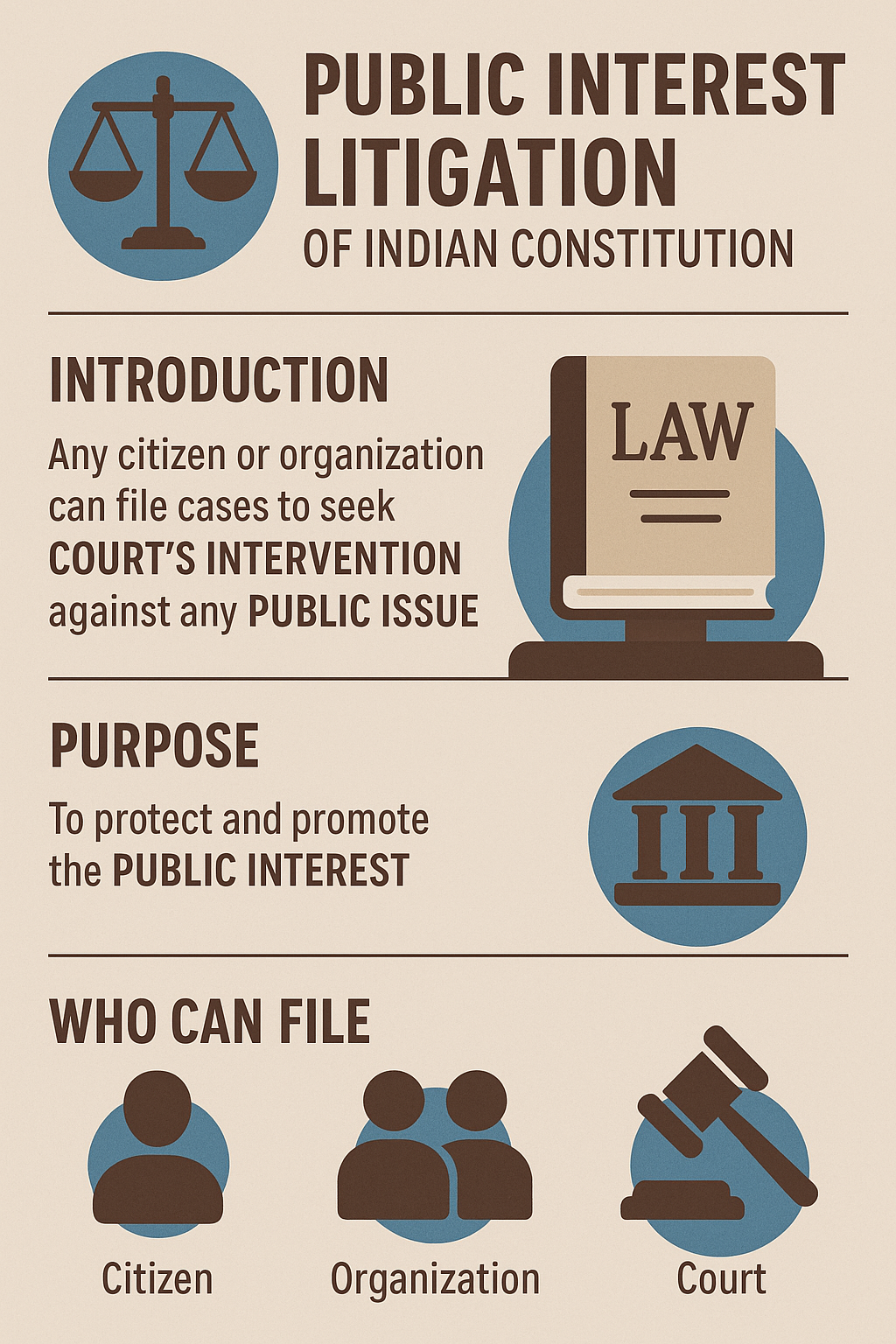

1) Orientation & Exam Relevance

Public Interest Litigation (PIL) is the Indian innovation through which courts relaxed traditional rules of standing to enable the protection of collective and diffuse rights. It is not a separate cause of action; rather, it is a procedural gateway to vindicate constitutional and legal rights of persons or groups unable to access courts due to poverty, disability, incarceration, marginalisation, or fear. For the UPSC Law Optional (Paper 1), you must be adept at weaving together: (i) the evolution of PIL, (ii) the tests for maintainability, (iii) innovations like epistolary jurisdiction and continuing mandamus, (iv) the subject-areas where PIL transformed governance (prisons, bonded labour, environment, right to food), (v) limits & safeguards against abuse, and (vi) concise case-law capsules.

2) Meaning, Objectives & Constitutional Location

Meaning: PIL is litigation undertaken not for a private remedy alone but for the enforcement of rights of a class/community or to address systemic illegality affecting the public interest. The petitioner may be a public-spirited individual, an organisation, or even the court acting suo motu.

Objectives: (a) open the doors of constitutional courts to the dis-empowered, (b) correct executive inaction or unlawful action, (c) fill normative gaps through guidelines where legislation is absent or delayed, (d) secure effective remedies through creative writs, monitoring, and compensation.

Constitutional location: PIL operates primarily through Article 32 (Supreme Court – right to move directly for enforcement of Fundamental Rights) and Article 226 (High Courts – writs for Fundamental Rights and “any other purpose”). It draws strength from the remedial architecture of the Constitution and the court’s duty to protect fundamental rights. Article 142 (complete justice) and the High Courts’ inherent powers often assist in fashioning effective remedies.

3) Evolution of PIL in India: Three Phases

Phase I: Access to Justice & Vulnerable Groups

The first wave concentrated on the rights of prisoners, bonded labourers, pavement dwellers, and children. Courts treated letters from activists as writ petitions; appointed commissions to verify facts; and issued broad directions on humane treatment, release/rehabilitation, and minimum standards. The jurisprudence insisted that dignity follows a person into prisons, and that economic compulsion amounts to forced labour.

Phase II: Environmental & Governance PIL

The second wave expanded to environmental protection, urban governance, public health, education, and administrative accountability. The court articulated principles like absolute liability for hazardous industries, polluter pays, and precaution; it monitored clean-up of rivers, air quality norms, and protection of heritage zones. In governance, the court issued directions for police reforms, transparency in public appointments/investigations, and safeguards against arbitrary surveillance.

Phase III: Calibration, Abuse Safeguards & Institutional Balance

A third, more restrained phase added filters to prevent misuse. Courts reiterated that PIL cannot be a proxy for private disputes, political vendettas, or publicity. They required bona fide intent, urged fact-based pleadings, discouraged bypassing alternative remedies without justification, and imposed costs in frivolous cases. The message: preserve PIL as a tool for systemic justice, not as an instrument for harassment or policy substitution.

PIL — Evolution at a Glance

Phase I

Access & Vulnerable

Phase II

Env. & Governance

Phase III

Calibration & Safeguards

Best ias coaching in hindi medium

Best mentorship programme for upsc

Best ias coaching in chandigarh

4) Locus Standi & Access to Justice Innovations

Traditional rule: Only a person whose own legal right is infringed could sue. PIL relaxed this by allowing public-spirited petitioners to represent those who cannot approach court. The petitioner need not prove personal injury but must show a direct nexus with a matter of public wrong or public injury and demonstrate bona fides.

Who can file? Individuals, NGOs, professional bodies, journalists, researchers — anyone acting bona fide in public interest. Courts may also convert letters, newspaper reports, or suo motu cognizance into PILs where egregious violations are evident.

Against whom? Primarily against the State and public authorities (Articles 12/226 wider understanding), but PILs have addressed private actors where public duties or state complicity exists (e.g., bonded labour, environmental harm), with the State being a necessary respondent.

5) Epistolary Jurisdiction, Amicus Curiae & Suo Motu

Epistolary jurisdiction refers to the practice of entertaining letters/postcards as writ petitions where grave rights-violations are disclosed. This innovation lowered procedural barriers: the form of the petition was subordinated to the substance of the grievance.

Amicus curiae & commissions: Courts often appoint amici, special commissioners or expert committees to collect facts, monitor compliance, and recommend solutions. These mechanisms substitute for formal discovery and allow continuous oversight in complex matters.

Suo motu cognizance empowers the court to initiate proceedings on its own where systemic illegality or constitutional concern is apparent.

6) Continuing Mandamus & Court-Monitored Compliance

Continuing mandamus is a distinctive remedial technique in PIL. Instead of disposing of the matter with a one-time order, the court keeps the case alive, issues interim directions, seeks periodic status reports, and calibrates relief until compliance is achieved. This device is particularly useful where problems are polycentric (e.g., pollution control, prison reforms, food security) and require iterative solutions.

7) Major Subject-Areas of PIL (with thematic case-capsules)

| Area | Typical Issues & Relief | Illustrative Case-Lines (1–2 sentences) |

|---|---|---|

| Prisoners’ Rights & Custodial Justice | Illegal detention, torture, overcrowding, legal aid, speedy trial, humane treatment. | Courts affirmed that fundamental rights do not stop at the prison gate; set guidelines on arrest/detention, legal aid, and prison conditions; appointed committees for inspection. |

| Bonded Labour & Child Labour | Identification, release, rehabilitation; minimum wages; enforcement of labour statutes; school access for rescued children. | The court recognised that economic compulsion and underpayment can amount to forced labour; directed governments to survey, free, and rehabilitate bonded labourers; emphasised accountability of district magistrates. |

| Environmental Protection | Air and water pollution, industrial hazards, waste management, heritage conservation, public transport emissions. | Principles articulated include absolute liability for hazardous industries, polluter pays, and precautionary principle; directions issued for industrial relocation, fuel standards, and river clean-up. |

| Women’s Dignity & Workplace Safety | Sexual harassment norms, safe workplaces, internal complaints committees, redressal mechanisms. | In absence of legislation, the court framed binding guidelines to prevent sexual harassment at workplaces, later codified by statute. |

| Right to Food & Social Security | Public distribution, mid-day meals, maternity benefits, nutrition standards, leakages and monitoring. | Through continuing mandamus, the court transformed schemes into entitlements, mandated periodic reporting, and created grievance mechanisms to address starvation and malnutrition. |

| Transparency, Investigations & Police Reforms | Insulation of investigative agencies, command/tenure stability, complaints authority, merit-based appointments. | Directives ensured operational independence and accountability of investigative bodies; in police reforms, the court mandated bodies and processes to limit political interference. |

| Urban Poverty, Evictions & Livelihood | Shelters for homeless, due process in evictions, rehabilitation, hawkers’ rights within regulatory frameworks. | The jurisprudence balanced planning with dignity, insisting on notice, hearing, and rehabilitation where appropriate; recognised livelihoods within reasonable regulation. |

| Education & Health | School infrastructure, teacher vacancies, RTE compliance; public health preparedness, hospital standards. | Court-monitored plans improved minimum standards and regular audits; directions often required budgetary transparency and standard operating procedures. |

8) Doctrinal Architecture: Standards & Tools Used in PIL

- Rule of Locus (relaxed): Petitioner may act in the public interest if the directly affected class cannot approach; verify bona fides and absence of personal gain.

- Evidence & Fact-finding: Courts rely on affidavits, government records, expert reports, and court-appointed commissions; pleadings must present verifiable material.

- Remedies: Classic writs (habeas corpus, mandamus, certiorari, prohibition, quo warranto) plus guidelines to fill legislative gaps, compensation for violations, monitoring via continuing mandamus.

- Standards of Review: Reasonableness and proportionality for restrictions; non-arbitrariness under equality; fair, just, reasonable procedure under life and liberty; public trust for natural resources.

- Separation of Powers Sensitivity: Courts prefer to catalyse executive/legislative action rather than govern; guidelines are meant as temporary standards until law is enacted.

9) Limits, Abuse & Safeguards: Keeping PIL Credible

Judicial Safeguards Implemented

- Bona Fides Test: Petitioners must disclose credentials, funding, and absence of personal gain; courts can reject at threshold.

- Pre-screening & Costs: Frivolous petitions attract exemplary costs; registries may screen maintainability.

- No Short-circuiting Statutes: Where specialised tribunals/statutory processes exist, courts insist on first using them unless gross illegality or fundamental rights urgency is shown.

- Separation of Powers: Courts avoid micromanagement; directions are calibrated, time-bound, and subject to periodic review.

- Evidence Discipline: Sweeping claims without material are discouraged; courts rely on expert bodies and verified data.

10) Drafting & Strategy for PIL (Exam-Oriented Framework)

When to choose PIL?

- When a class of persons faces rights-violations and cannot approach court due to poverty, disability, or fear.

- When executive inaction creates a systemic failure (e.g., non-implementation of statutory duties).

- When there is an urgent threat to life, liberty, environment, or public health.

Essential Ingredients of a PIL Petition (for exam answers)

- Title/Parties: Petitioner with credentials; appropriate respondents (Union/State/authority).

- Standing: Explain why the affected class cannot approach; assert bona fides.

- Material Facts: Crisp narrative; attach credible reports/affidavits; identify statutory duties breached.

- Constitutional Hooks: Articles 14, 19, 21, 23, 24, 39, 47, etc., as relevant; specific statutory provisions.

- Prayer for Relief: Targeted writs (mandamus/certiorari), guidelines (where legal vacuum), monitoring schedule, compensation (where appropriate), creation of oversight mechanisms.

- Interim Relief: Immediate protection (stay, status quo, supply of food/medicine, stay on polluting activity, constitution of committee).

11) Landmark Case-Law Capsules (1–3 lines each)

- Prisoners’ Rights line: Courts held that fundamental rights extend to prisoners; mandated humane treatment, legal aid, and periodic inspections; condemned custodial violence.

- Hussainara Khatoon series: Recognised speedy trial as a component of Article 21; ordered release of undertrials incarcerated for periods longer than the maximum sentence.

- PUDR & Bonded Labour cases: Underpayment vis-à-vis minimum wages can amount to forced labour; directed surveys, release, and rehabilitation.

- M.C. Mehta series (environment): Evolved absolute liability for hazardous industries; embedded polluter pays and precaution; court-monitored clean-ups and emission norms.

- Vishaka guidelines (workplace safety): Framed binding guidelines to prevent sexual harassment in the absence of legislation; later implemented by statute.

- Right to Food line: Converted schemes into entitlements; ensured mid-day meals, PDS reforms, and grievance redressal through continuing mandamus.

- Prakash Singh (police reforms): Mandated state security commissions, fixed tenures, transparent appointments, and independent complaints authorities.

- Vineet Narain (investigations): Issued directions to secure independence of investigative bodies; insulated investigative decision-making from extraneous influence.

- Transparency & Surveillance cases: Laid down safeguards for wire-tapping and data collection; emphasised proportionality and oversight.

- Urban homelessness & shelters: Directed creation/upgrade of night shelters; set minimum standards and monitoring frameworks.

12) Critiques, Course-Corrections & Future of PIL

Key Critiques

- Judicial Overreach: Guidelines may resemble policy-making; risk of courts stepping into executive shoes.

- Institutional Capacity: Courts may lack expertise to design/monitor complex schemes; dependence on committees may create implementation gaps.

- Elite Capture: PIL agendas sometimes mirror urban middle-class concerns more than those of marginalised communities.

- Floodgates & Frivolity: Popularity invites misuse for private feuds or political battles.

Course-Corrections & Good Practices

- Calibrated Relief: Prefer standards & nudges to direct management; sunset clauses for guidelines once law is passed.

- Evidence-Led Orders: Rely on independent experts; insist on transparent data and measurable milestones.

- Respect for Forums: Do not bypass statutory regimes lightly; encourage tribunal expertise when appropriate.

- Community Voice: Involve affected groups in compliance committees; ensure remedies match lived realities.

Mind Map: PIL — Concepts, Tools & Cautions

Locus & Access

Epistolary & Suo Motu

Continuing Mandamus

Subject-Areas

Standards & Tools

Limits & Safeguards

13) Selected Previous-Year Themes (Law Optional)

- “Trace the evolution of Public Interest Litigation in India and critically evaluate its impact on access to justice.”

- “Explain the development of epistolary jurisdiction and the device of continuing mandamus in PIL.”

- “PIL should redress public wrongs, not private grievances.” Discuss with reference to maintainability and bona fides.

- “In what ways has PIL shaped environmental jurisprudence in India?”

- “Critically examine safeguards introduced by courts to prevent abuse of PIL.”

- “Discuss the interplay of Articles 32 and 226 in the context of PIL and the role of High Courts.”

14) Probable Questions (Upcoming Prelims & Mains)

Prelims-type (MCQ) — with Answers

- “Epistolary jurisdiction” refers to:

(a) Letters treated as petitions in public interest

(b) Power to punish for contempt

(c) Advisory opinions to the President

(d) Reference jurisdiction under tax statutesAnswer: (a)

- Which of the following is not a typical PIL ground?

(a) Systemic violation of fundamental rights

(b) Private service dispute between two employees

(c) Environmental degradation affecting a city

(d) Non-implementation of statutory welfare dutiesAnswer: (b)

- “Continuing mandamus” is best described as:

(a) A one-time injunction

(b) Ongoing judicial monitoring with periodic directions

(c) Advisory directions without binding effect

(d) Criminal contempt proceedingsAnswer: (b)

- Under which Articles do constitutional courts primarily entertain PIL?

(a) 32 & 226

(b) 323A & 323B

(c) 131 & 136

(d) 124 & 214Answer: (a)

- Which is a valid safeguard against abuse of PIL?

(a) Absolute ban on NGO petitions

(b) Imposition of costs in frivolous cases

(c) Refusal to hear any matter involving policy

(d) Only Attorney General may file PILAnswer: (b)

Mains-type (Analytical)

- “PIL is a constitutional catalyst, not a substitute for governance.” Discuss with examples and doctrinal limits.

- Critically evaluate the role of expert committees and amicus curiae in fact-finding and compliance in PIL.

- How has PIL jurisprudence balanced rights-protection with separation of powers? Illustrate with guidelines-framing cases.

- Discuss PIL’s contribution to social welfare entitlements and the risks of judicial populism.

- “Environmental PILs established foundational principles that now pervade regulatory law.” Explain.

15) FAQ & Quick Tips

Is PIL a separate cause of action?

No. PIL is a procedural posture that relaxes standing so that courts can address public wrongs affecting those unable to litigate. The underlying cause is the infringement of constitutional/statutory rights or public duties.

Can PIL be used for private service disputes or land matters?

Ordinarily, no. Such matters should go through statutory/ordinary forums. Courts reject attempts to dress up private disputes as PIL.

What is the difference between Article 32 and Article 226 in PIL?

Article 32 is itself a Fundamental Right to move the Supreme Court for enforcement of FRs. Article 226 gives High Courts wider writ powers — for FRs and “any other purpose.” Strategically, High Courts are often the first forum.

When do courts create guidelines?

Where there is a normative vacuum and urgent rights-protection is needed, courts may lay down interim guidelines as stop-gaps pending legislation, aligning with constitutional values.

How to conclude a PIL answer?

End with a balanced line: courts must remain catalysts for rights-protection while respecting institutional limits; safeguards against abuse preserve PIL’s legitimacy.

No Comments