09 Aug Relationship between Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles, and Fundamental Duties

Relationship between Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles & Fundamental Duties (UPSC Law Optional – Paper 1)

Part IV

Part IVA

Harmonious Construction

Basic Structure

31C

Proportionality

Positive Obligations

Transformative Constitutionalism

Constitutional Morality

Table of Contents

2) Constitutional Map: Parts III, IV & IVA

3) Historical Debates & Early Jurisprudence

4) From Conflict to Reconciliation: Doctrinal Phases

5) DPSPs as Sources of Positive Duties under FRs

6) Fundamental Duties: Meaning, Use & Limits

7) Doctrines Connecting the Three

8) Substantive Domains where the Triad Interacts

9) Federal, Fiscal & Institutional Dimensions

10) Answer-Writing Framework & Case Capsules

11) Selected Previous-Year Themes

12) Probable Questions (Prelims & Mains)

13) FAQ & Quick Tips

Tags (SEO)

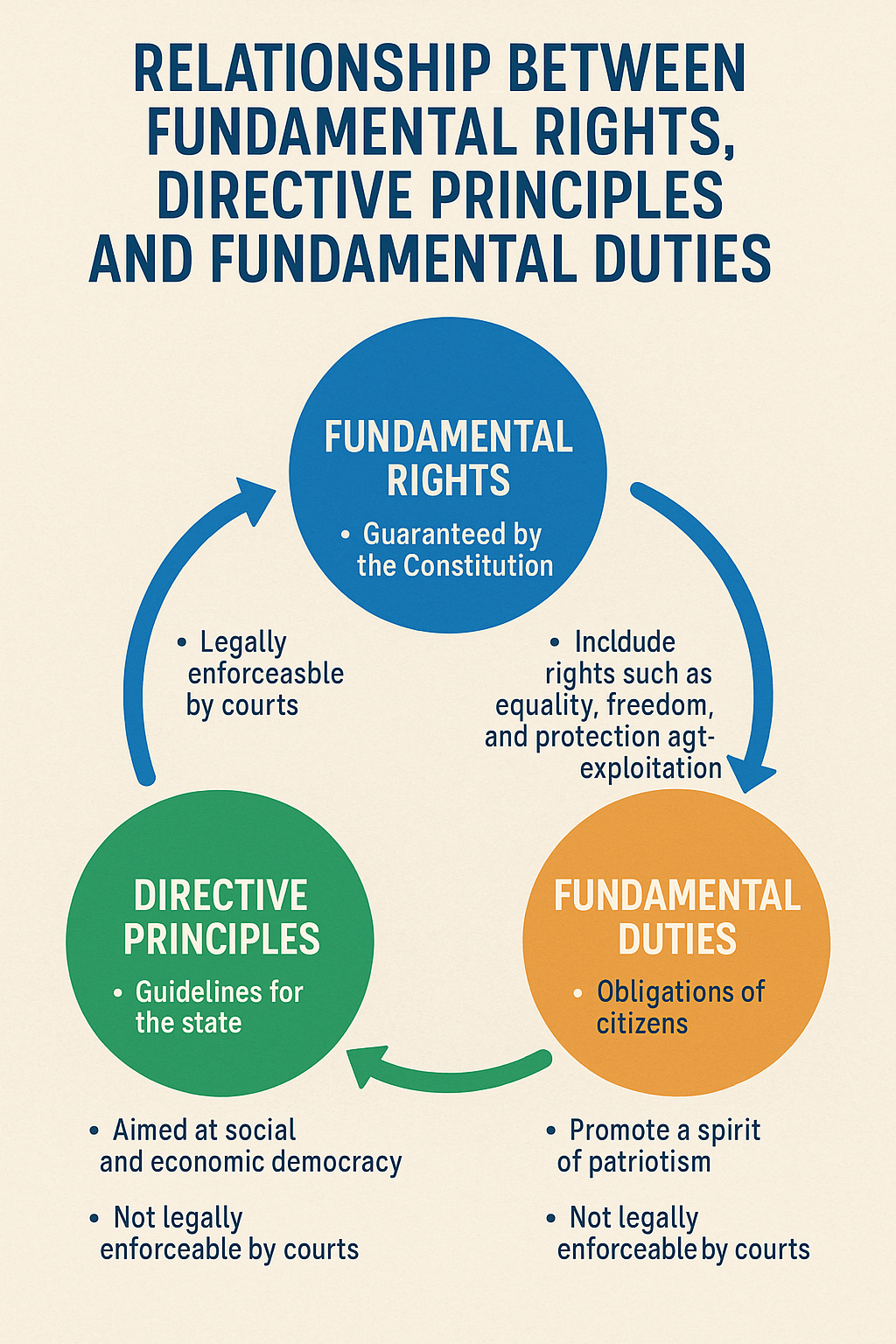

India’s Constitutional Triad: FRs ↔ DPSPs ↔ Fundamental Duties

Fundamental Rights

Directive Principles

Fundamental Duties

DPSPs guide interpretation → positive obligations

Duties inform restrictions & civic responsibility

FRs limit means; DPSPs state ends

Duties align citizen conduct with constitutional values

1) Orientation & Exam Relevance

Why this topic matters: Questions on the relationship among Fundamental Rights (FRs), Directive Principles of State Policy (DPSPs), and Fundamental Duties (FDs) are perennial in UPSC Law Optional (Paper 1). You are evaluated on your ability to (a) set out the text and structure (Parts III, IV and IVA), (b) capture the doctrinal evolution from a perceived conflict to harmonisation, (c) connect the triad through cases and principles (harmonious construction, proportionality, basic structure, non-retrogression, constitutional morality), and (d) apply these to live areas—education, health, environment, affirmative action, social security, and public order. This note provides an exam-ready account, with clear sub-headings, short case capsules, and visual anchors to tighten retention.

2) Constitutional Map: Parts III, IV & IVA

Part III (Articles 12–35): Fundamental Rights. Enforceable claims against the State (and in some instances with horizontal reach). Core clusters: equality (14–18), freedoms (19), criminal process protections (20), life and liberty (21, 21A, 22), exploitation (23–24), religion (25–28), culture/education (29–30), and remedies (32; with 226 at the High Courts). They are justiciable; violations invite writs and structural remedies.

Part IV (Articles 36–51): Directive Principles of State Policy. Non-justiciable obligations guiding legislation and governance. They articulate the Republic’s ends: social, economic and political justice (e.g., 38), equitable distribution of material resources (39(b)), prevention of concentration of wealth (39(c)), living wage and humane conditions (43), participation of workers in management (43A), public health and nutrition (47), and protection of environment (48A). DPSPs are not mere “pious hopes”; they set standards against which State policy is constitutionally evaluated and judicially interpreted when FRs are at stake.

Part IVA (Article 51A): Fundamental Duties. Non-justiciable duties of citizens: abide by the Constitution (a), cherish ideals (b), defend the country (d), promote harmony (e), value rich heritage (f), protect environment (g), develop scientific temper (h), safeguard public property (i), strive for excellence (j), and ensure education for children (k). Duties lack direct coercive enforcement, but courts draw upon them to interpret rights and assess the reasonableness of restrictions and the content of civic responsibility.

3) Historical Debates & Early Jurisprudence

In the Constituent Assembly, there was broad agreement that a modern Republic should enshrine both justiciable rights and socio-economic directives. The controversy was over how to operationalise welfare within a rights-based framework. The adopted design entrenched enforceable FRs and non-justiciable DPSPs, expecting the political branches to achieve directive goals progressively, while courts secured a minimum floor of liberty and equality.

Early post-Constitution litigation framed FRs and DPSPs in adversarial terms. Courts struck down policies pursuing directive goals when they violated FRs, emphasising that non-justiciable directives could not override enforceable rights. Yet, even in that phase, the spirit of the directives influenced interpretation, especially where the rights text allowed balancing through “reasonable restrictions” or where the content of a right had to be elaborated.

Best Law optional coaching for upsc

Best law optional teacher for upsc

Best coaching for law optional

4) From Conflict to Reconciliation: Doctrinal Phases

Phase I — Tension & Textual Formalism

In the initial years, courts tended to treat FRs and DPSPs as separate compartments. When a law pursuing a directive goal directly conflicted with a right—say, equality or property (as it stood then)—the right typically prevailed. This phase safeguarded individual guarantees but occasionally stalled redistributive policy, prompting constitutional amendments that sought to immunise certain welfare laws from rights review.

Phase II — Towards Balance: Basic Structure & Harmony

The middle phase generated the pivotal idea that the identity of the Constitution consists in a balance: FRs supply enforceable restraints and dignity-based liberty; DPSPs supply the telos of social justice; neither can be so truncated as to damage the basic structure. This catalysed harmony. Courts began to read rights in the light of directive values: e.g., liberty with social justice, equality with substantive measures, life with health and environment.

Phase III — Integrative Jurisprudence: Positive Obligations & Proportionality

In the mature phase, courts explicitly derived positive obligations of the State from DPSPs, while enforcing them through the language of rights. Right to education, right to health, environmental safeguards, workplace dignity, and social security were articulated as components of Articles 14/19/21, with DPSPs operating as interpretive anchors. The modern method is proportionality: the State may pursue directive ends, but the means must be suitable, necessary (least-restrictive), and balanced against rights costs. This turns a binary “rights vs. directives” clash into a structured justification exercise.

Rights ↔ Directives — From Tension to Harmony

Phase I

Tension & Formalism

Phase II

Basic Structure & Harmony

Phase III

Proportionality & Duties

5) DPSPs as Sources of Positive Duties under FRs

Education: Long before Article 21A, courts read a right to education within Article 21 (life and liberty), inspired by DPSPs such as 41 and 45. This right was later given explicit textual form, but the doctrinal move mattered: DPSPs enriched the content of a right and justified structural orders (school infrastructure, mid-day meals, teacher appointments, neighbourhood schools) through continuing mandamus. The lesson: even when a directive is non-justiciable, courts may convert its core into a rights-based obligation where dignity and equality demand it.

Health, nutrition and public health: Article 47’s emphasis on raising nutrition and public health has profoundly influenced Article 21. Right to emergency medical care, hospital standards, transparency in procurement, minimum services during strikes, maternal health entitlements, and road-safety obligations have been judicially framed by referencing directive goals and reading them into the logic of life and dignity.

Environment: Article 48A (and the duty in 51A(g)) pairs with Article 21 to ground the “right to a clean and healthy environment.” Courts have required polluters to remediate damage, mandated environmental impact assessments with meaningful public participation, and insisted on precautionary planning where irreversible harm looms. DPSPs supply the public interest content; rights supply the enforceability.

Livelihood & humane conditions: Directives for living wage and humane work (38, 39, 41, 43) inform rights against arbitrary eviction, minimum wages, bonded labour abolition, and workplace safety. Courts have upheld worker-protective regulations (e.g., safety codes, maternity benefits) by balancing business freedom under Article 19(1)(g) with directive-driven public interest, applying proportionality to test reasonableness under Article 19(6).

Social justice & distributive fairness: Articles 39(b)–(c) and the scheme of land and resource reforms aimed to prevent concentration of wealth and secure distribution of material resources for the common good. Over time, this distributive vision has shaped expropriation, compensation design, and scrutiny of monopolistic privileges, while keeping a firm eye on due process and equality.

6) Fundamental Duties: Meaning, Use & Limits

Nature: Fundamental Duties do not create direct, standalone liabilities for citizens. They are a catalogue of civic obligations and constitutional values. Their legal significance lies in interpretation: duties help courts understand the reasonableness of restrictions (e.g., on speech in sensitive contexts), calibrate remedies (e.g., public-property vandalism), and develop positive programmes (e.g., environmental awareness, scientific temper).

Illustrative uses: Duty to protect the environment (51A(g)) has been invoked to sustain conservation measures, waste management, and behavioural nudges; duty to develop scientific temper (51A(h)) supports evidence-based policy, counter-misinformation campaigns, and curricular reforms; duty to safeguard public property (51A(i)) justifies recovery of damages from riot-related vandalism subject to due process; duty of parents to provide education (51A(k)) aligns with the 21A mandate.

Limits: Duties cannot be used as blunt instruments to curtail rights beyond constitutional tests. They are contextual aids, not override clauses. When duties are cited to restrict rights (say, speech or association), the restriction still must satisfy the textual grounds and the proportionality standard. The Constitution remains a charter of reasons, not raw power.

7) Doctrines Connecting the Three: Your Ready-Reference

- Harmonious Construction: Read Parts III, IV, and IVA together to maximise coherence. When two interpretations are possible, prefer the one that advances directive goals without stifling core rights.

- Basic Structure: The balance between FRs and DPSPs is part of the Constitution’s identity; neither can be destroyed by amendment or policy. Duties contribute to constitutional identity by articulating civic commitments.

- Proportionality: Modern rights review. State must show a legitimate aim (often a directive goal), rational connection, necessity (least-restrictive means), and overall balance.

- Non-retrogression: Once rights are expanded (e.g., health, education, environment), the State should not roll back essential protections without weighty justification.

- Positive Obligations & Reasonableness: FRs are not only shields; they also impose duties to arrange institutions and budgets to make rights real, especially under Articles 14 and 21, illuminated by DPSPs.

- Constitutional Morality & Transformative Vision: Interpreting the text in a manner that furthers dignity, equality, and fraternity; Duties amplify the ethical horizon of the Constitution.

- Severability & Reading Down: Where a welfare law pursues directive ends but uses overbroad means, courts often prune the excess (sever/“read down”) rather than invalidate the entire scheme.

8) Substantive Domains where FRs, DPSPs & Duties Interact

(A) Education

Education is the canonical example of rights-directives convergence. DPSPs (41, 45) furnished the State’s goal of universal education; courts enforced its minimums under Article 21 (and later 21A), requiring infrastructure, teacher-student ratios, inclusive admission policies balanced with minority autonomy (29–30), mid-day meals for nutrition and retention, and transparency in fee regulation. Duties strengthen the culture of schooling: parents’ duty (51A(k)) and civic respect for learning environments.

(B) Health & Nutrition

Public health directives (47) mesh with Article 21 to generate enforceable entitlements: emergency care, ambulance availability, clinical standards, patient rights charters, maternal health benefits, disease surveillance, and accountability mechanisms. Duty to develop scientific temper (51A(h)) supports vaccination drives and evidence-based advisories. Restrictions on harmful substances (liquor, tobacco) are defended with reference to directive aims and proportionality.

(C) Environment & Climate

Environment is a synergy zone: 48A (directive) + 51A(g) (duty) align with 21 (right to life). Courts have demanded cumulative impact assessments, precaution in siting hazardous units, restoration funds, afforestation, and commons protection (public trust doctrine). Competing rights (livelihood, trade) are balanced using proportionality and phased compliance—means must be as gentle as possible while achieving the end.

(D) Labour, Social Security & Livelihood

Directives on humane work (39, 41, 42, 43, 43A) animate labour codes, workplace safety, social security, and participation in management. Courts calibrate Article 19(1)(g) freedom with consumer protection, worker dignity, and fair competition. Street-vending, gig work, and platform economies are assessed with the same grammar: does the regulation pursue directive ends proportionately?

(E) Equality & Affirmative Action

Equality jurisprudence has moved from formal sameness to substantive measures, drawing from directive commitments to social justice (38, 46). Reservations, targeted scholarships, and welfare schemes must align with equality’s purpose and efficiency in administration, but their directive anchor helps justify the object while rights guard the method from arbitrariness.

(F) Culture, Religion & Social Reform

Balancing religious freedom (25–28) with directives on social reform (e.g., 44 in debates on uniform civil code; 39 on dignity in family law; 51A(e) on harmony) illustrates the triad’s delicacy. Courts distinguish essential practices from secular practices amenable to regulation and use proportionality to mediate conflicts.

(G) Governance Standards & Transparency

DPSPs about just governance (38, 39A, 50) inform due process, separation of powers, legal aid, tribunal design, and judicial independence. Fundamental Duties bolster civic cooperation with institutions and promote ethical public life (scientific temper, excellence, protection of property). Together, they frame a constitutional culture where State reasons its actions and citizens participate responsibly.

9) Federal, Fiscal & Institutional Dimensions

Federalism: Many directives require State-level action (health, education, local government). The Union sets floors (national schemes/standards), while States tailor implementation. Courts respect this distribution but demand that minimum constitutional essentials are met everywhere. Inter-governmental cooperation and Finance Commission allocations become instruments for delivering directive goals.

Budget & capacity: Transforming directives into reality needs money, staff, and systems. Judicial orders increasingly focus on institutional design: named officers, milestones, dashboards, social audits, and independent oversight. The idea is to move from declarations to delivery.

Local bodies & community role: Panchayats and municipalities are crucial for last-mile execution—nutrition, sanitation, primary education, water supply, and environmental upkeep. Duties translate into citizen participation—reporting leakages, maintaining public assets, and adopting pro-environmental behaviours.

10) Answer-Writing Framework & Case Capsules

Six-step framework for any FR–DPSP–FD question

- Define the relationship: FRs are enforceable means; DPSPs set non-justiciable ends; Duties cultivate civic responsibility that enables both.

- Textual anchors: Cite relevant Articles—e.g., 14/19/21 for rights; 38, 39(b)–(c), 41, 43, 43A, 47, 48A for directives; 51A(a)–(k) for duties; 32/226 for remedies; 31C for immunisation debates.

- Evolution: Phase I (tension), Phase II (balance as identity), Phase III (integration via proportionality and positive obligations).

- Doctrine: Harmonious construction, basic structure, proportionality, non-retrogression, reading down/severability.

- Application: Pick one domain (education/health/environment) and show how a directive goal is realised through rights-compliant means; mention duties as supporting norms.

- Close: “Ends of social justice cannot be pursued by unconstitutional means; equally, rights are not sterile—they are the instruments through which directive values become lived reality.”

Case-law capsules (1–3 lines each; quote the holding, not the rhetoric)

- Balance as identity: Courts affirmed that the Constitution’s basic structure includes a balance between Part III and Part IV; neither can be eviscerated by amendment or policy.

- Right to education: Recognised as part of Article 21 (before 21A); later constitutionalised; State obligations include infrastructure, teacher norms, and inclusion, calibrated with minority autonomy under 29–30.

- Right to health & emergency care: Public health (47) read into life and dignity (21); hospitals must provide timely treatment; procurement and standards are judicially monitored in structural cases.

- Environment: 48A + 51A(g) + 21 → right to a clean environment; principles of precaution, polluter pays, and restoration; proportional regulation of industry and urban activity.

- Legal aid & speedy trial: 39A strengthened access to justice; delay and denial of counsel violate 21; structural remedies include legal services authorities and monitoring.

- Affirmative action & equality: Equality’s purpose embraces substantive justice; reservations must be anchored in evidence and efficiency; directives justify ends; rights police the means.

- Labour dignity: Living wage and humane conditions (39, 41, 42, 43, 43A) animate workplace safety, maternity relief, and participation; restrictions on business are tested for reasonableness under 19(6).

11) Selected Previous-Year Themes (Law Optional)

- “Explain the jurisprudence on reconciliation between Part III and Part IV. How has the basic structure doctrine shaped this relationship?”

- “Discuss the role of Directive Principles in expanding the content of Article 21 with examples.”

- “‘Fundamental Duties are not enforceable, yet they matter.’ Analyse with reference to the reasonableness of restrictions and public interest.”

- “Trace the development from a ‘rights v. directives’ tension to harmonious construction, with leading case-law.”

- “Short notes: (a) Article 31C (b) Non-retrogression (c) Reading down to save welfare statutes.”

12) Probable Questions (Upcoming Prelims & Mains)

Prelims-type (MCQ) — with keys

- Which of the following is correct about the relationship among Parts III, IV and IVA?

(a) DPSPs override FRs whenever there is a conflict

(b) FRs and DPSPs must be read harmoniously; Duties assist interpretation

(c) Duties are enforceable like FRs

(d) DPSPs are mere policy statements with no constitutional roleAnswer: (b) - Article 48A is most closely connected with which right?

(a) 21A (b) 25 (c) 21 (d) 17Answer: (c) — the right to life and a clean environment is read with 48A. - Which pair is correctly matched?

1. Article 39A — Legal aid 2. Article 47 — Public health 3. Article 43A — Worker participation

Options: (a) 1 only (b) 1 and 2 only (c) 2 and 3 only (d) 1, 2 and 3Answer: (d) - Which statement best reflects the modern test?

(a) Reasonable classification alone

(b) Proportionality for balancing directive aims with rights

(c) Strict separation with no overlap

(d) Literalism over purposivismAnswer: (b) - Which is a Fundamental Duty?

(a) To vote in elections (b) To pay taxes (c) To develop scientific temper (d) To obey all executive ordersAnswer: (c)

Mains-type (Analytical)

- “Ends of social justice cannot be pursued by unconstitutional means.” Discuss this statement with reference to proportionality and Article 31C debates.

- Evaluate how Duties under Article 51A have influenced environmental and educational jurisprudence. Should courts rely more on Duties or keep them as soft constraints?

- “Article 21 has become a bridge between FRs and DPSPs.” Critically examine with reference to health, education, and environment.

- How should courts approach economic regulation that pursues directive goals but restricts Article 19 freedoms? Propose a structured test and apply it to a hypothetical.

- Do you agree that the ‘balance’ between Parts III and IV is part of the basic structure? Provide reasons and practical implications.

13) FAQ & Quick Tips

Are DPSPs judicially enforceable?

No. They are non-justiciable. However, they guide interpretation of FRs and can be implemented through legislation; courts hold the State accountable for reasonableness in pursuing directive ends.

Can Fundamental Duties be enforced directly?

Not as standalone causes. They inform interpretation—especially reasonableness of restrictions—and inspire legislative and executive programmes.

What is the best one-line relationship?

FRs are the enforceable means constraints, DPSPs set the ends, Duties supply the civic ethos that sustains both—together they produce a welfare, rights-guarding Republic.

How to earn extra marks?

Use 3-part structure in every paragraph: text → doctrine → application. Drop precise Articles and a case capsule per theme. Conclude with proportionality or constitutional morality.

No Comments